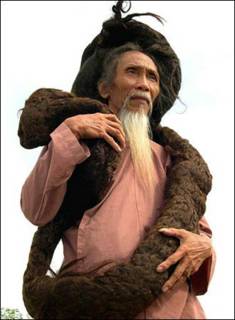

Longest Hair in the World

Report on Pay Rates for Freelance Journalists

Last year, the National Writers Union Delegates Assembly appointed a committee to study pay rates for freelance journalists in order to determine a minimum recommended rate.

Our research was motivated by a strong sense among our members that freelance rates don't provide freelancers with even a moderate income. We believed that rates have not kept up with staff salaries in recent years. We had also heard widespread claims that freelance rates had not gone up since the 1960s. So we set out to see if there was any basis in fact for these beliefs.

In addition to researching what freelancers need to charge per word to make a living, we aimed to put the information into context: Have freelance pay rates increased, stagnated, or decreased since the 1960s? What do staff writers make? What do other college-educated professionals make? How much can publishers afford to pay writers?

We discovered that the situation is even worse than we had thought. In real dollars, freelance rates have declined by more than 50 percent since the 1960s. And while rates have gone down, publishers are getting more for their money.

This report deals only with rates, not rights, but it must be noted in passing that publishers are asking for and getting more secondary rights for the same dollar that once bought only one-time rights. Writers who used to compensate for the poor pay rates at newspapers by reselling articles to multiple markets can no longer do so.

How much do full-time journalists need to charge to make a moderate living?

Freelance writers spend a tremendous amount of time looking for work (researching and pitching articles) and revising. While some articles can be done in a week and others may take three months, for most full-time freelance writers, selling and writing 3,000 or 4,000 words a month is about the best that they can expect to do -- two feature articles or the equivalent in smaller pieces. (This is more than most magazine staff writers write -- which is about 2,500 words a month.)

At this level of output, a rate of a dollar a word means a gross income of $36,000 to $48,000 a year, out of which has to be taken expenses, insurance, and other benefits. This is the equivalent of earning a salary, with benefits, of about $30,000 to $40,000 a year. So for a college graduate working as a full-time freelance writer to bring in even a moderate income that includes benefits, requires at least $1 a word.

The median income of full-time, college-educated workers in the US is around $50,000, plus benefits. So to earn as much as the average college graduate would require somewhat more, between $1.25 and $1.60 a word.

How much did magazines pay in the past?

In real dollars, magazines used to pay far more than they do today. Freelancers' rates have been declining since the mid 1960's in real terms--for more than 35 years. For example, Writer's Market, which reports what magazines themselves say they pay, shows that writers' rates at the top magazines have declined by two-thirds to four-fifths since 1966, far more than the approximately 20% loss in real hourly wages that the average American worker suffered during the same period. Writers' real rates were falling even in the late '60s and early '70s when most workers' wages were rising.

As an example of the generation-long losses, in 1966 Cosmopolitan reported offering $0.60 a word, while in 1998 they reported offering $1 a word. In the meantime, the buying power of the dollar fell by a factor of five. So Cosmopolitan's real rates fell by a factor of three. Good Housekeeping reported offering $1 a word in 1966 and the same $1 a word in 1998- — a full 80% decline in real pay.

Another way of looking at these figures is to translate them into 2001 dollars. In terms of these dollars, Good Housekeeping was paying $5 a word in 1966.

To fully compare these figures with rates actually paid today, one must take into account that that the magazines' reports to Writer's Market underreport rates by as much as a factor of two in general, as demonstrated by the NWU's own ongoing survey of what writers are actually paid by the same magazines. Such underreporting of rates occurred in 1966 as well, so actual rates for Good Housekeeping, in 2001 dollars, may well have been higher than $5 a word.

How much do magazines pay their staff writers?

The average wage for staff positions ranges from $35,270 for news reporters to $45,500 for staff writers, plus benefits, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Based on our examination of largely staff-written monthly magazines, the average staff writer's output is between 20,000 to 30,000 words per year. This means that per-word rates average around $1.60 a word, not including the value of benefits. If benefits are included, this works out to close to $2 a word. (To be conservative, we used the Bureau of Labor Statistics' figure for staff writers. At the actual magazines we surveyed, most staff writers are paid at least twice that, which would mean per-word rates come out to about $4 a word.)

How much can publications afford to pay?

We also compared publication income with words of text published to get an estimate of income per word and to determine what fraction of total revenue is paid to writers. For example, for Discover magazine, 500 pages of ads a year at $50,000 per full-page ad gives $25 million a year in gross revenue. (This underestimates their income, because half-page ads cost two-thirds as much as full-page ads). Since the magazine has one million subscriptions at $25 per year, it has another $25 million a year. (This ignores newsstand sales, which make the total even larger.) Divide by 500 pages of text a year at 800 words per text page and Discover's income is more than $125 per word. Discover pays its writers $1 a word. So they pay their writers less than 1% of their gross income. If they paid them 15% of gross income, the way book publishers manage to and still turn handsome profits, they would be paying at least $19 a word.

The numbers are remarkably similar for Forbes, which also charges $50,000 a page for full-page color ads and also earns roughly the same income from ads as from subscriptions.

In general, advertising and subscription revenues are proportional on a per-word basis to circulation--the more readers, the more income per word. We estimate that publications can afford to pay 15% to 30% of their total revenue to their writers. This means that publications, except for those with fewer than 25,000 readers, can afford to pay $1 a word. This is confirmed by the fact that some magazines listed in the NWU Guide to Rates and Practices as having ad rates under $5,000 a page (the lowest category) did in fact pay as much as $1 a word four years ago, although rates have fallen since then. It also means that writers are being paid no more than 1% to 2% of total income, basically a tenth of what the book publishing industry pays.

For the largest magazines, the gap is even worse. Magazines like Good Housekeeping and Women's Day with ad rates of $200,000 a page and more and as many as eight million readers are earning something like $500 a word. Yet they pay freelancers $1 to $2 a word, less than 0.5% of revenues. If they paid the writers 15% of revenue, freelancers would be getting $75 a word at these publications.

What about newspapers? The New York Times takes in about $40,000 per ad page or about $2 million per issue, about comparable to Discover, Forbes, and Good Housekeeping. The Times metro edition hits about a million readers. With $1 million or more in subscriptions per issue, not counting newsstand sales, and 30 pages of text in a daily edition, this works out to at least $38 a word. So at 15% of income, the Times could afford at least $6 a word, not the 30 cents to a dollar it normally pays freelancers.

Thus a minimum rate of $1 a word is no hardship for publications and will be a first step to recovering the ground writers have lost over the past thirty five years.

NWU Report on Pay Rates for Freelance Journalists

No comments:

Post a Comment